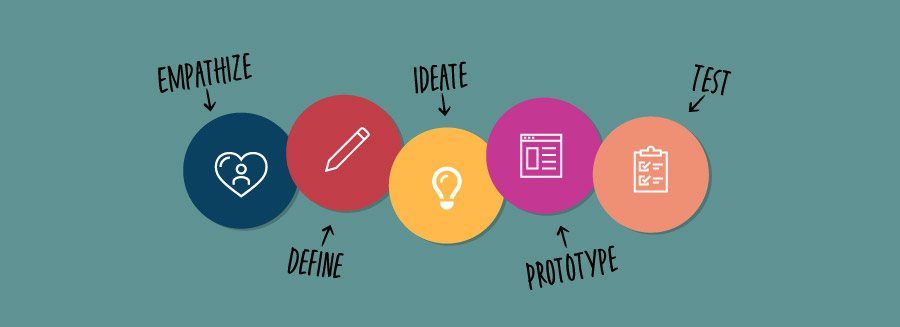

In K-12 education, students often learn structured processes like writing a five-paragraph essay or applying the scientific method in labs. With the rise of creative, project-based learning, another valuable framework deserves attention: the Design Thinking method. Widely taught in design schools and used across creative industries, this five-step process—empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test—can be modified for users of all ages. By incorporating Design Thinking into project-based learning, educators can bring structure to potentially chaotic projects while guiding and assessing students’ creative work more effectively.

I advocate for using Design Thinking in the classroom because I’ve seen firsthand how it emphasizes the creative process, where real growth occurs, over the final outcome. A flashy solution often fails to show a deep understanding of the problem, the creative challenges students overcame, or the iterations of prototyping and testing involved. Design Thinking also encourages divergent thinking, exploring many ideas rather than rushing to a single solution. I found that in group settings, the framework amplified quieter voices, preventing dominant students from steering the group toward an early, mostly unvetted idea.

Process

To see how the Design Thinking method works, we’ll use the issue of veterans facing homelessness or housing insecurity as our example. It’s an important, real-world problem that’s perfect for showing how Design Thinking can guide us through finding creative, meaningful solutions.

1 Empathize

The first step in Design Thinking is to understand the needs, experiences, and challenges of the problem you’re trying to solve via observation, research, and interviews. In our example, this involves talking to veterans experiencing homelessness, listening to their stories, and observing their day-to-day struggles.* Students might learn that some veterans find traditional shelters unwelcoming because they are often located in city centers that can be too chaotic and noisy for those suffering from PTSD. Have your learners cast a wide net during this step and gather as much information as they can to ensure they go beyond surface-level assumptions.

*Ensure you properly prepare students to respectfully interview their subjects, being mindful of sensitive topics and potential challenges. Emphasize asking thoughtful questions, listening carefully, and explaining how participants’ input aids their learning process.

2 Define

With the information gathered, the next step is to synthesize the findings and articulate a problem statement. Synthesizing can take many forms: card sorting, affinity mapping, persona creation—the goal is to determine the main problem. Once identified, have your students draft a problem statement. For our example, it might read like this: “Veterans experiencing homelessness need housing options that address their unique needs: mental health resources and living quarters that don’t trigger emotional distress.” A well-defined problem statement narrows the focus, ensuring students target the real issues (not their preconceived notions) with their creative solutions.

3 Ideate

This is the brainstorming phase, where learners should generate as many solutions as possible without judgment. Encourage students to sketch, build upon each other’s ideas, and think far outside the box. I sometimes found students hesitant to push the boundaries of what is possible, so you might need to jump in here to help expand their brainstorm. There are no bad ideas; it’s about quantity, not perfection, at this stage. Next, it’s time to rein in the ideas and land on a feasible solution or two. In our example, ideas could range from building tiny home villages tailored for veterans to creating mobile outreach units that connect them to mental health resources.

4 Prototype

Prototyping involves creating simple, tangible versions of your ideas to test them. For instance, students might build a mock-up of a tiny home unit using cardboard or design a mobile app with free drag-and-drop design software that matches veterans with mental health services. From my experience, students often default to building a refined product. Thus, remind your learners that these prototypes don’t need to be polished—they aren’t going to market. Prototypes are just tools to explore how ideas might work in practice during the final phase.

5 Test

Finally, it’s time to have your students test their prototypes with the people they’re designing for—in this case, veterans. Feedback might reveal that while tiny homes offer privacy, they also need communal spaces for building a sense of community. Or they might learn that the mobile app needs to function offline for veterans without reliable internet access. Remind your students that designers almost never get it right on their first attempt. Testing is meant to help refine ideas to ensure the final solution truly meets users’ needs, not merely to validate one’s efforts thus far.

When a prototype (inevitably) proves unsuccessful, have your students return to one of the previous steps and work their way through to the end of the process again. Perhaps they need to return to ideating (Step 3) and move ahead with a different solution from their brainstorming. Or maybe a return to prototyping (Step 4) is all that’s needed to make a round of tweaks before testing again.

Outcomes

By following the Design Thinking process, students are encouraged to slow down and carefully consider the needs of users and the perspectives of others before rushing to implement their ideas. For students who struggle with more traditional learning methods, Design Thinking offers a more flexible, hands-on approach that values and rewards exploration and creativity—not expertise and polish. Additionally, for students who struggle with creative assignments, the framework provides structure and scaffolding to make the process less intimidating.

Evaluating

When evaluating creative work, the focus should be on critiquing, rewarding, and celebrating the process, not merely the outcome. Did students approach the empathizing stage with open-ended questions? Was the ideation phase successful in considering a wide, inventive range of ideas? This shift in focus alleviates concerns about whether the final prototype is “successful” and encourages students to embrace the journey of trial, error, and reflection.

Want to see the Design Thinking process in action? Check out the solutions students at Hillbrook School in Los Angeles created for other members of their school community.

Looking for resources to help introduce the Design Thinking method to your students? For younger learners, consider this approach that uses a picture book as a springboard. For older students, check out the Wallet Project from Stanford University.