In honor of Banned Books Week, let’s talk about how we can use book challenges as an opportunity for growth in our school communities.

The question of what our kids read in school is one that is increasingly contested and elicits very strong emotional responses from caregivers, educators, students, and the general public. Book challenges can create angry divisions in a school community and can leave educators feeling defeated, but how might we turn these difficult situations into something positive? Can we use these challenges as an opportunity to reimagine why and how we select, evaluate, and teach with books?

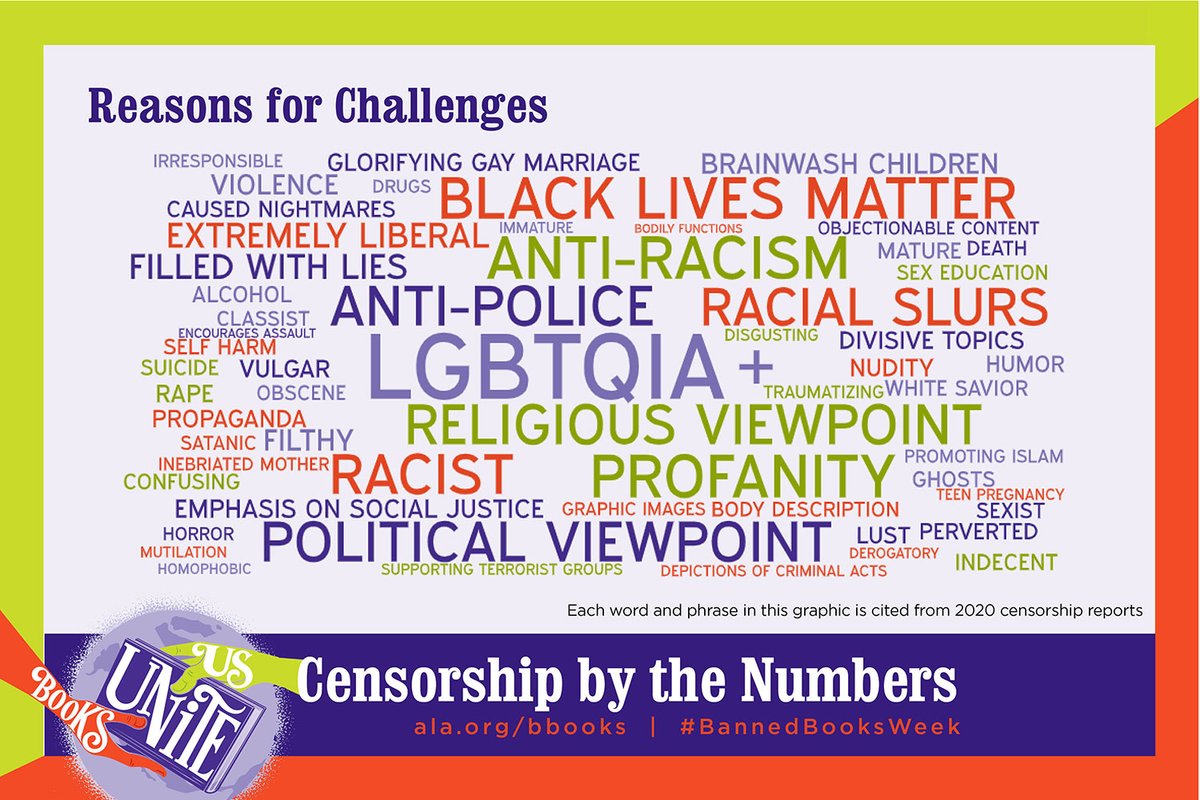

The desire to protect our children from being exposed to things that could harm them spans all communities and cultures. Sometimes that protection comes in the form of attempting to shield them from ideas that may seem inappropriate for their age level or harmful to their development. Community members across the political spectrum have advocated for the removal of books from school libraries or curriculum that address topics they consider inappropriate, immoral, problematic, or not aligning with community values. Even if books are not formally challenged, the threat feels ever present, so educators will often “self-censor” books or topics that may be controversial. Whether the censorship is direct or indirect, the books most likely to be challenged, removed, or avoided are books written by/about people of color and members of the LGBTQ community.

Book challenges are incredibly difficult for educators and administrators to navigate. And while community members absolutely have a right to voice their concerns, at the end of the day, it’s the educators that must make decisions, rooted in their professional training and expertise, about the best ways to educate children. And while the mistrust from community members can feel disheartening, we can use this productive struggle as the engine to drive a collective reimagining of why and how we use books in our schools.

Creating Goals to Guide Book Selection/Review

Similar to a school’s mission statement or strategic plan, educators should be empowered to consider and establish collective goals and guidelines for curating library collections and instructional materials. Everyone benefits when educators are given the time and space to come together and use their expertise with intention. Book selection for our classrooms and libraries must always be rooted in larger goals for our students’ intellectual and emotional growth and their right to an equitable school environment.

How a school goes about forming these guiding principles will not be the same everywhere. Each community will have unique needs and concerns that educators will want to address. And while creating and agreeing on goals for your school is obviously going to be a complicated process, we do not need to reinvent the wheel. A great place to start is to explore the Social Justice Standards from Learning for Justice. While these guidelines are not specific to book selection, they allow us to be reflective about the purpose that books serve for our students and how they can be a tool in helping students of any age gain a deeper understanding of complex social inequality issues. Using a social justice lens reframes the debate on books with complex themes. Instead of asking simply, “Is this appropriate for students in this school?” we can ask questions like, “Does this book help students be exposed to the diversity of people in/outside of our community? Does this book help students understand the experiences of groups whose stories have been historically marginalized?”

And while the outcome (written goals and guidelines) is obviously important, the process is just as important for educators. Being given the time and space to collectively reflect on your school’s intentions for the books you buy and how you use them is incredibly valuable and should be repeated at least every few years so that the goals can shift and change as the school community and priorities change.

Once goals and guidelines have been agreed upon, use them to inform the creation of a review policy for when books or other resources are challenged. Again, you need not start from scratch. NCAC offers guidelines and a sample review policy from an Iowa school district. Ensure that your review committee does not exclude librarians and classroom teachers in the relevant age level or subject area. They should be positioned as the experts on the educational value of a text (or lack thereof) as it contributes to students’ intellectual and emotional growth. Additionally, NCAC strongly recommends including high school students on review committees. Make sure to amplify student voices in any way you can throughout the process–give them a genuine platform and take their input seriously. Community members should also be included on review panels, but should not outnumber trained educators.

When books are challenged, district/school leaders will sometimes respond by immediately pulling the book from circulation or the curriculum until it can be reviewed. This can be extremely frustrating for educators who selected that book for very specific reasons. If educators and administrators are more aligned, if they are operating with collective goals for book selection in mind, these types of knee-jerk reactions will be less common. Additionally, when a community member challenges a book, instead of responding with defensiveness, we can interpret their concern as a signal that we have not clearly communicated our goals with them and how this specific book aligns with those goals.

Even if collective guidelines are established for book selection and are communicated clearly to the school community, book challenges will still happen. But the more we can empower educators to make informed choices with intention, the more successful we will all be in navigating these challenges in a way that centers our students’ needs.

Integrating Support for Complex Issues

The most common argument for removing books from schools is that they are inappropriate for young people. In the most generous interpretation of that argument, the concern is that children just don’t have enough context to interpret/evaluate/make sense of the complex topics in a given book. When we hear this type of argument from community members, we can interpret it as constructive feedback that we, as an entire school, have an opportunity to do more to help our students understand complex issues and, by extension, do a better job of helping community members understand WHY students need to understand these complex issues.

Let’s take an example of a community member seeking to remove a book about a transgender child from a school library. If they are surprised to see a book with those themes in the school library, that can be a message to educators and administrators that the school could be doing more to convey the importance of learning about gender diversity. Transgender or agender people are a part of every community. Young people need to have a basic understanding of the nuances of their lives and their identities. If a school clearly conveys to all community members, in their policies and practices, in the information they send home, etc. that understanding gender diversity is important, some community members may still have personal objections, but they will be less likely to feel that a book is subversive or misaligned with the school’s values.

Providing context can also mean that we reevaluate the older books we are using, even if they are considered classics, for harmful stereotypes of historically marginalized groups. When we reexamine older books through a social justice lens, we ask different questions about the value of a book and we take the voices of marginalized groups seriously when they raise concerns. This reexamination certainly doesn’t mean that older books will always be removed from classrooms or libraries. Instead, we should take these types of concerns as a signal that as a school, we can be doing more to prepare students to read these books and understand the books’ themes in their historical context. For example, several older books have been challenged recently because they contain racial slurs and caregivers are concerned about how teachers are approaching their instruction of these books. If a review committee decides to keep a book like this in the curriculum or in the library, this is an important opportunity for a school to be intentional about helping students (and the entire school community) understand the history of racial slurs and why their use today is so nuanced and complicated. Additionally, if older books with these themes are being assigned to students, they could be paired with modern-day depictions of similar themes to provide students with a well-rounded understanding of this issue in context.

Establishing collective goals for book selection and intentionally providing context on complex issues are not easy changes to make within schools, but they are incredibly important. Debates about what is appropriate for our children to read push us to reflect on the larger purpose of books for our children, the power of books to open their minds and their hearts, and our role in helping them understand what they read. We can take these very difficult situations and turn them into positive changes for our students, our teachers, and the entire school community.

For additional reading on these topics, see my blogs on partnering with caregivers, laying the groundwork for discussing complex topics, helping students understand inequality, and moving beyond diversity goals.