As an English and speech teacher for mostly sophomores, I found myself frustrated when students seemed to be just going through the motions, looking for every shortcut available (ahem, Sparks Notes). I wanted my students to be genuinely curious about the literature we were examining or to be genuinely excited to write for an audience. The speech teacher in me wanted students antsy for their turn to communicate a message important to them and to move their peers in some way. I definitely didn’t enjoy all the absent students who were home with speech anxiety sickness on presentation day. Fortunately for both my students and me, I had an opportunity to be part of a group of English teachers who decided to take a different approach—one with inquiry as the vehicle to drive learning. I thought this month, I could share the top ten ways we made inquiry work in our 10th grade ELA classroom as well as secondary ELA classrooms I have had the opportunity to support.

First, if you aren’t clear on what inquiry is and what it looks like in a classroom, please pause for five minutes and watch John Spencer’s brilliant video. Next, you might be wondering why you might look to incorporate an inquiry stance for English/Language Arts. I found that as soon as I started making shifts, I noticed more energy, joy, excitement, and productive struggle in our learning environment. Even when I was struggling to make it work, we still had a lot more fun. The quality of the discussions, writing, analysis, discourse, and presentations were markedly higher than when I was taking a more traditional approach. This was enough for me to abandon traditional and embrace inquiry.

Here are my Top 10 Ways to Make Inquiry Work:

1.Quit teaching the book and instead focus on the benchmarks. I had to move away from teaching Of Mice and Men or Lord of the Flies or any of the other 10 books I had to choose from for English/Speech 10. When I was teaching novels, I found myself trying to help students get all of the great stuff I had gotten from the book in the 20 times I had read it in just their first read. It was killing the book and killing all student motivation to read it. Not to mention the moment reading is assigned, student motivation decreases. So instead, I focused on the benchmarks within the ELA standards and used the books as tools for student advancement. If students were citing textual evidence as they made claims about the author’s purpose, it did not matter if what they were saying was something I had noticed or taught previously.

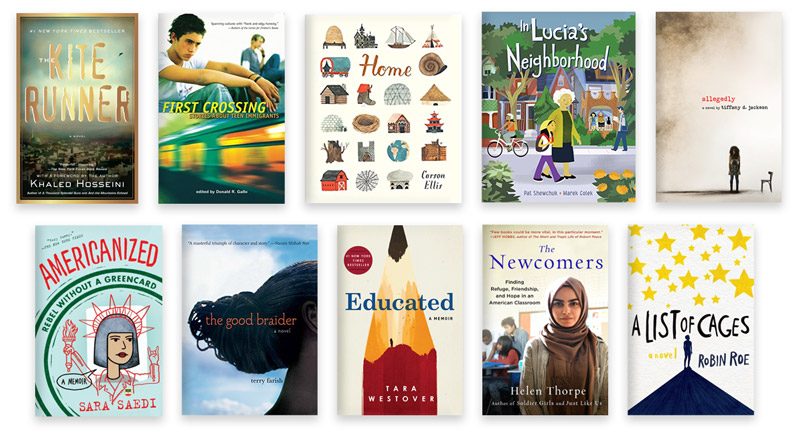

2.Create a unit of study around a provocative question. Creating a unit of study led by an overarching question that would intrigue students gave me the freedom to stop teaching the novel and instead create conditions for students to grow in their ELA skills. I stopped teaching my Of Mice and Men unit and instead moved to a unit with the question: “What does it mean to be our ‘brother’s keeper’ and should we?” Or, “What is an individual’s duty to others?” Instead of teaching The Kite Runner, we explored: “How do we define home? Is it beneficial to understand others’ definition of home and consider revising our own definition?”

3.Move away from the whole class novel and create engaging text sets instead. Once we had overarching questions, we then moved to creating text sets. This gave students choice in what to read to explore the question and to practice ELA standards. Choice is a critical component of inquiry-based instruction. Here is an example of texts we could explore with our Finding Home unit. Notice there are picture books. Adolescents enjoy shared reading experiences and picture books provide fertile ground for rich conversation. Other texts might be used in small groups for book clubs. In this example, Kite Runner is a choice for students, not a novel we would all be reading together.

4.Stop teaching book clubs. When students were placed in book clubs, I wanted to foster conditions for authentic conversation about the books in relation to our essential question and the priority standards we were working on. I used to put students in groups and assign roles like travel tracker—you track the plot, word wizard—you share new words you’ve learned, decision detective—you decipher the major decisions being made by characters in this section, discussion director—you lead the discussion by preparing open-ended questions ahead of time. As I listened to the discussions, I found that they really were just exercises in reading completed homework out loud, one at a time, around the circle. When moving to an inquiry unit of study, all students are responsible for tracking their thinking as they read and sharing what they are thinking when in discussion. If you are interested in a rubric I created and found helpful for practice discussions, feel free to contact me for it. I am happy to send it to you in an email.

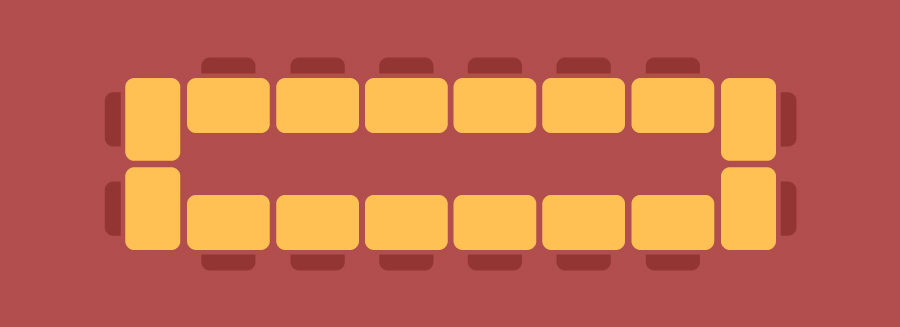

5.Rearrange your classroom. This one is so simple. Just put your desks in triads or quads for collaboration and remove the rows. Maybe you do this already. I had spent my entire first 10 years with my desks in rows because it was neat and I was afraid of side conversation. Changing up the arrangement of my room reminded me every day that students needed to do the talking, questioning, and inquiring; not listen to me share all my insights from the book(s) we were reading.

6.Reward student questions over student answers. I started designing assessments where students would gather and share their questions. We worked on using questions to dive deeper into the material and to create new and better questions. I gave students points for providing questions based on what they were reading and researching instead of giving any kind of quiz where they needed to provide answers to my questions. This blog article by Jackie Walsh gives great advice for embracing student questions in the classroom.

7.Opt for authentic learning over as/if scenarios. So often in my ELA classroom I would start a writing activity with “Imagine you. . .” These hypotheticals were not exciting for my students. I would be teaching students to have productive discussions and provide them with tasks where they pretended to be lobbyists advocating for change in legislation. Students didn’t see personal relevance and it became an exercise in “get ‘er done.” When I moved instead to having students explore real issues in our school or local community, researching solutions and discussing ways to promote real change, it led to authentic discussion and motivation on several students’ parts to put their ideas into action. One group didn’t like the competition culture that came from top students in the school vying for valedictorian. As a result, the group convinced the school to instead recognize all students who reach cum laude, summa cum laude, or magna cum laude status.

8.Reconsider your definition of assessment. Long story short, I threw away multiple choice and short answer tests and replaced them with performance assessments guided by rubrics that students used throughout the unit as they practiced for final summative assessment, aka game day. Let’s say students are being asked to “Analyze the impact of a text’s publishing date on its current validity and credibility, in literature, social studies, or science” (MN Academic Standards, 2020). Students can practice this with short texts, poetry, images, and excepts while the instructor gives formative feedback. This supports a learning culture. Then students can confidently develop their performance assessment because they know exactly what is expected to perform at mastery.

9.Step back and let students wrestle with ideas. I remember vividly supporting a colleague in her sixth-grade reading class where students were taking on an inquiry approach to the study of the short film and picture book, The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore. On this given day, students were to research several allusions that appear in the short film including Pop Goes the Weasel, The Wizard of Oz, and Hurricane Katrina. Students were actively researching on their iPads, sharing discoveries, asking questions, and overall buzzing about the topics. At one point a student yelled out, “Hey! Hurricane Katrina hit both New Orleans and Los Angeles!” The old me would have swooped in to correct the student’s misconception. I mean, we can’t have him go home thinking Los Angeles was part of the Hurricane Katrina catastrophe, can we? But instead, my colleague and I stepped back and listened to a peer question him.

“Where do you see that it hit Los Angeles? That seems far away,” she said.

“It says so right here,” pointing to his iPad. “New Orleans, LA.”

“LA stands for Louisiana,” she clarified in a direct, but supportive way.

“Oops. Hey everyone! I was wrong. Hurricane Katrina didn’t hit Los Angeles,” the student yelled having no qualms about admitting he clarified his learning and didn’t want anyone else carrying the misconception home. Certainly, if misconceptions linger too long, we want to dip in with direction or more resources so students can discover the right answer.

10.Change the way you plan your lessons. A final way to make inquiry work is to change the way you plan your day with students. In her book So What Do They Really Know, Cris Tovani encourages us to really focus on what students will be doing and learning, and less on what we will be teaching. This shift requires us to put together resources and provide a lot of time for student practice. She advocates for beginning with an opening and short mini lesson, then moving students into guided practice for the bulk of the time, and finally ending with a debrief. It is during work time that more targeted instruction can happen for individual students or small groups of students. Check out this explanation from Tovani’s blog to learn more.

Inquiry might be a little messy, but isn’t learning supposed to be? If you have questions, want to learn more, or are interested in having me or a team member support you in this work, please reach out to us!